I am a great advert for not following one’s own advice.

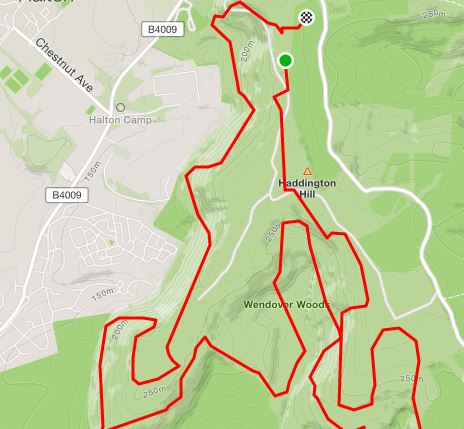

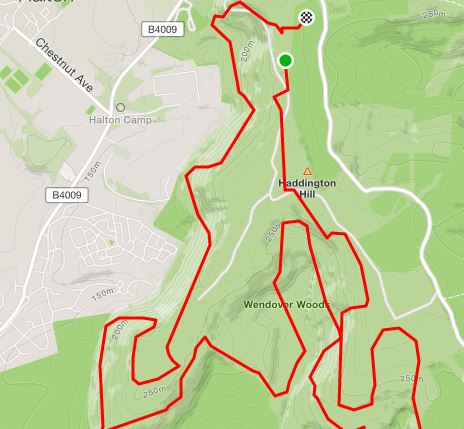

After a miserable year of non-running, not enough running, running poorly, running out of time to run, I started 2017 with the intention of maintaining a mile a day run streak and completing the Centurion 50 mile Grand Slam – four fifty milers staged throughout the year on the South and North Downs, the Chiltern Hills and Wendover Woods – to give a shot in the arm of my athletic career. What could go wrong?

My times on each race grew progressively slower, my recovery less and less effective and my training became what can most politely be described as sparse. The motive behind the run streak was primarily to readjust my life priorities around a job that often needs responsive, erratic hours and little hope of setting a routine; if I’m maintaining a run streak then I have to find at least ten minutes a day to myself in order to keep it going, and that ten minutes of much needed headspace. The logic was sound, to me at least, to lean on my addictive nature: I’m more likely to prioritise the integrity of the streak than my physical health, career, relationship, mental health. That logic proved to be as effective as taking morphine for a broken leg and continuing to run. It resolves the short term obstacle as the expense of the long term solution.

I miss my daily run, desperately. It had become a single junk mile per day dragging myself around the pavement in my area for the sake of the streak, it was less than useful in athletic terms. Nevertheless, I saw that mile the way an ex-pat misses sugary treats from home – more value to the soul than to the body. If he could get a truckload of Swizzel-Matlows shipped to Outer Mongolia he’d eat the lot in one sitting but it wouldn’t stave off hunger in the long run. The pleasure of those homely treats would last as long as the treats themselves, then immediately be replaced by nausea, rotten teeth and malnutrition.

I even tried other means of improving my fitness; this time experimenting with a low-carb diet and low-HR training method (Maffetone) which, for the brief period I sustained it, sustained me very well. The problem was that my lifestyle doesn’t exactly make finding carb-free food easy, and my commitment to the program had even less integrity than Kelly-Anne Conway’s commitment to the truth. Once again I am made out a fraud, espousing a philosophy I cannot myself live by.

So two days after Chiltern Wonderland I decided to break the streak. I realised I was suffering classic overtraining symptoms – I realised it many months ago, but accepted it only when the CW50 nearly hobbled me. Good old fashioned rest would be my one last hope to get through the fourth and toughest of the fifty mile grand slam series; most likely I am the only person surprised to discover that it worked. Almost.

So, having made more of the runs I could do with three or four 5+ mile runs a week instead of seven 1 mile runs, I barely ran at all for the two weeks prior to the race. It coincided with a bout of flu and two big weeks at work, building up to the biggest broadcast of the year, so the timing actually worked out quite well for me. I wasn’t exactly resting, but at least I wasn’t stressing out about finding that elusive ten minute window for a run round the block. And besides, I did a lot more managery pointing at things than being on my feet doing actual work things – all in the name of athletic improvement you understand. The flu bit was more of a concern, but by the Friday I was back to being able to sleep lying down and breathing through my nose sometimes. Win.

For only the second time ever, Andy was roped in to crew. There was a logistical reason for this – I couldn’t get there in time by public transport, and if I drove there I’d be unlikely to be able to drive back – but his support turned out to be so much more than just chauffeur. The format of the race – five 10 mile loops returning to the same start/finish point – meant that he could base himself at one place, be on hand to bring me food or extra kit, give a quick systems check at the end of each lap and chivvy me along. And spend the intervening three hours listening to podcasts in the car.

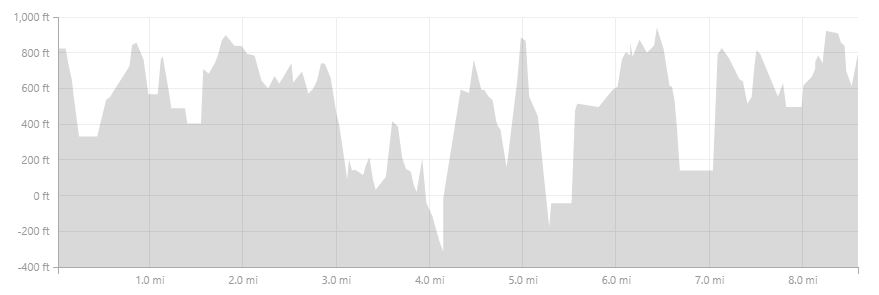

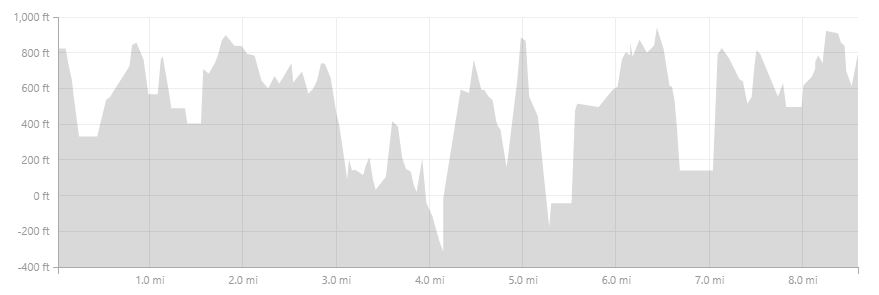

We lined up for lap one in the first few blinks of daylight – it was still dark when I picked up my bib number – and received our race briefing. Unlike previous Centurion race briefings I’ve heard James Elson deliver, this one consisted of about three sentences: the route is marked to the nth degree, you’re gonna see everything five times so if you don’t you’ve gone wrong, and take it slow. The 10 mile loop would have a net descent profile in the first half and a net ascent in the second, helpfully broken up by a checkpoint at mile 5.5, but either way you look at it there’s a lot of ups and downs. I’d printed myself a course profile and timings for the aid stations for a 12hr, 13hr, 14hr and 15hr average pace with the hope that I’d be hovering around 13hr pace to begin with and have enough buffer by the end. The original intention had been for me to carry this so I’d know where the climbs would be, but I realised that a) I’d learn pretty quickly where those climbs where and b) that sort of information might be more useful in Andy’s hands, who would read it and be able to work out how my pace, than mine, who would look at it and think “huh, some numbers”. Instead, I set my Suunto going and loaded up the WW50 gpx to follow.

On the basis of the pacing chart Andy told me I was due in to base no sooner than half past ten, or two and a half hours in. Any earlier and I’d be in trouble with him; too much later and I’d be in trouble with myself. Having been up since half 5 to drive me here he was already struggling to stay awake; he waited to wave me off then retired to a McDonalds he’d spotted about five miles back for a dirty breakfast. Far be it from me, An Athlete, to be jealous of a Maccy D’s breakfast, but damn that was a hard thing to hear as I set off down the muddy, near-freezing path.

For the first lap I tried to pay close attention to the course, the twists and turns especially, knowing those to be the easiest thing to miss in the dark, and didn’t get to do as much chatting as I’d have liked. I actually knew a fair few people there: Cat Simpson from Fulham RC was tipped for the win and her and Louise Ayling had both been out on Wednesday night headtorch runs; Awesome Tracey was somewhere in the pack, a double double Grand Slammer I’d met during CW50; and my lucky charm Ilsuk Han popped up at the halfway checkpoint as a volunteer.

As far as relying on my watch went the theory was sound, the practicality less so. I’ve been dicking around with my Suunto settings trying to get my watch to last for a whole 50 mile race, after it had run out of battery before the end of the first three; normally it’s fine, but the nav function is a bit of a power vampire. There is however an option to make the battery life last longer by reducing the accuracy of the signal: by picking up my location every 10 seconds instead of every second I figured I’d still get an accurate enough measurement (this finish wasn’t exactly going to be measured in fractions of a second) and hopefully have it running long enough to be able to use the average pace setting. Yes, that sounds foolproof.

Louise, who’d volunteered the race the previous year and was well briefed, mentioned that we would see the checkpoint two miles before we actually reached it thanks to a neat little detour loop. That kind of route info is really useful to know, relative measurements which can’t be tricked rather than saying that such and such aid station is at mile x. You don’t know if that mile marking is measured from the start or measured by an interval from the previous one, if your watch is on the ball or if it’s missed a chunk of signal, or if the volunteers are just trying to be optimistic. So after a fun little trundle through the woods, a couple of sharp ups and a lot of long steep downs (fuck I love those) I turned a left to see the checkpoint directly ahead by a line of trees, and a pink arrow pointing right up a steep slope. Goody gumdrops.

Even after having run it multiple times, I’m still not sure now if that ascent is the first big one on the course or if it’s just the first one that makes you swear. Especially as you’ve seen the urn boiling away and the plates of cookies and cheese sandwiches laid out, waiting for you, and then you’re forced to leave them behind because no reason. The climb starts gentle, gets progressively steeper, reaches the top and then presents you with another sharp upward tick. Then you scoot down to the bottom again, about 20 minutes after you saw the checkpoint. And that’s about a mile. We were directed off to the right again for another hands on knees hike up to the Go Ape climbing attraction, back down through a carpet of gorgeously soft pine needles, and round and round the garden until the checkpoint finally appeared. I checked my watch. 4.5 miles, nearly 16mm pace and around an hour and ten minutes passed.

Tits.

Worryingly, that’s lightly slower than I’d planned at this point even taking that one climb into account – I’ve only just got to the end of the “easy” half, and now I’ve got that and another mile to go, mostly uphill? This isn’t good. I mean I’ve taken it plenty easy and I’m still well within pace, but once I take exhaustion into account I’m going to go downhill fast. Wait, that’s the wrong phrase entirely. Uphill, slow. OK, don’t worry about that now. Already I was mentally comparing the image of the elevation profile with my experience and finding that it wasn’t as gruelling as I’d expected. Physically tough, certainly, but the sort of challenge I was really enjoying getting my teeth into. So I’d obviously got my calculations wrong – it was a 4.5 mile/5.5 mile split, not the other way around, and I’d need to pace the second half accordingly. Never mind, keep plugging on.

I knew that we would have at least three pretty monster hills towards the end of the second half, and sure enough I was back on my knees hiking up what seemed like a sheer cliff face. Not too bad underfoot now, but I suspected it would get a lot slippier before the day was out and it had been churned up a few times. Still the climb itself, though slow, was pretty satisfying. Next up came a really beastly climb, even steeper and slippier than the last, but again I paced myself through it (and tried not to look down) and within about ten minutes I was at the top. But the final one was the real killer. Short, sharp, nowhere near as vicious as the first two and it even had handrails. Sounds easy, right? Wrong. My legs were spent by this point. It was like death by a thousand papercuts. I’ve never used a handrail so vigorously nor been so convinced that it would pull out of the ground like a rotten weed in my hand.

When we reached the top I overheard another runner called Wendy, a friendly and cheerful voice who had for some reason chosen this to be her first ever fifty mile race, mention that we had just over a mile to go. I checked my watch. It still said 7.5 miles, and only two hours in. What’s going on? But sure enough, a few moments later we passed her support crew cheering on from the peak of the final climb and they confirmed that there was less than a mile to go. We passed through a gate and ran a perfectly flat gravel loop circumnavigating the field where the base and car park were situated, and just two hours and seventeen minutes later I was waving frantically at Andy, simultaneously surprised and pleased to see that he’d been optimistic enough to get to the tent early.

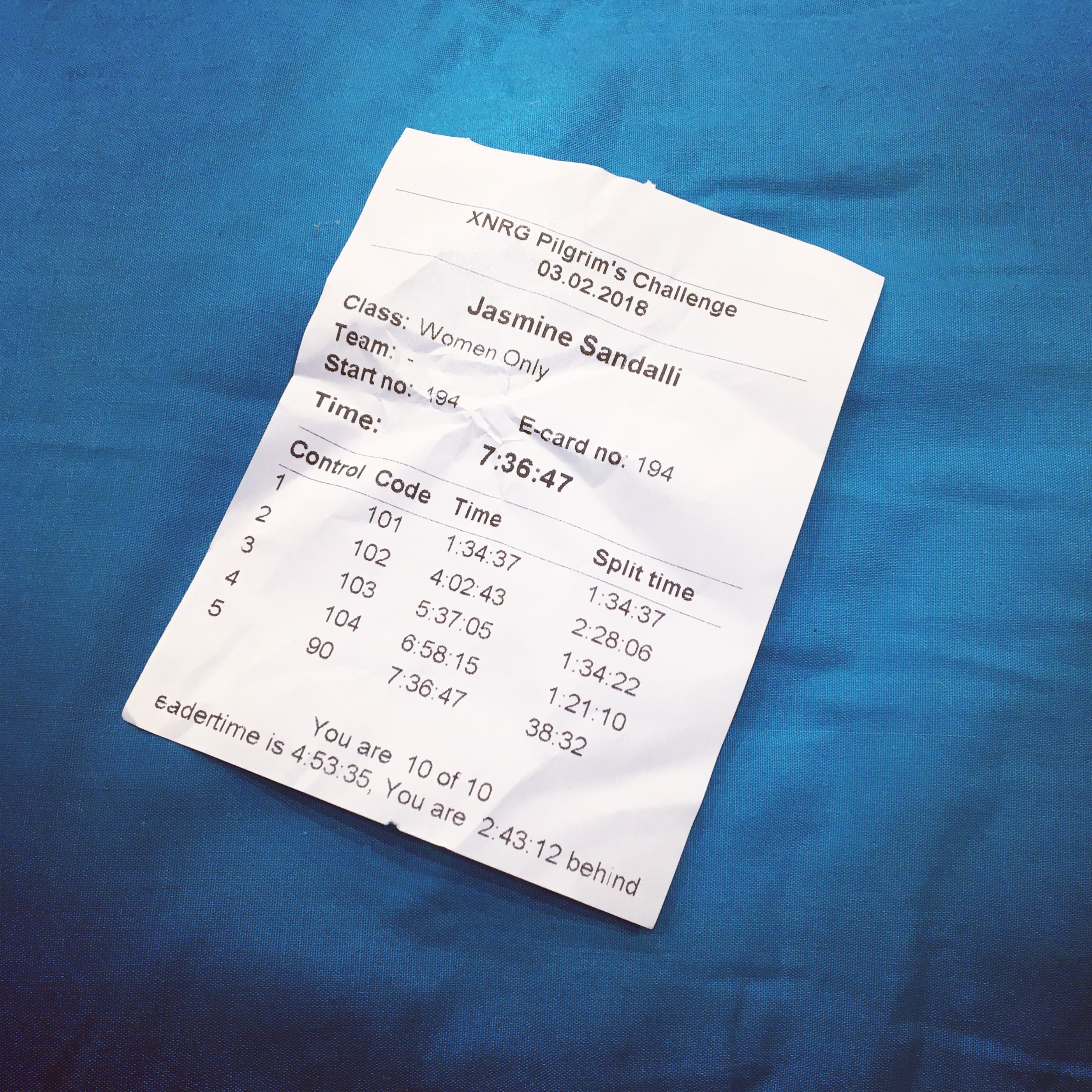

As usual, I’m not sure how I missed the obvious signs but my watch was way off. Showing just under eight and a half miles at the end of the lap, and therefore calculating the pace according to the time (which was correct) I’d been under the impression I still had another mile and a half to go and was behind my ideal pace. Instead, what happened was that I averaged 13.5 minute miles for the first lap – it also meant I wasn’t wrong about the position of the halfway checkpoint either, it was at 5.5. Another lesson in trusting your maths over your tech. I paused briefly to get an update on the frontrunners, three bites of Mars bar and a handful of cookies. Even with the time cushion there was no time to sit though, my bladder having finally kicked into gear, so I stopped for a loo break and switched off my obviously useless watch. From now on I’d rely on Andy and the only two timing points I needed to hit each lap.

I’d made a point of chatting with people when they happened to run at my pace but not trying to keep up with anyone for company – I know that I’m much faster than a lot of people on the downhills thanks to my devil-may-care style and quads of granite, but almost as slow going uphill as the wildlife. At least for the first couple of laps my pace would have to be exactly that – my pace – and the final lap or two would be trudgeville for most of the field anyway. However I did find myself falling in step with Tracey Watson, on aggregate at least; we were at the same pace on the flat but when we came to a downhill I passed her and when we went back uphill again she overtook me with ease. Tracey is a legend among Centurion runners already, as she was going for the 2017 double grand slam – that’s right, the final race of eight that year to complete both the 100 mile and 50 mile grand slam – but the more remarkable thing is that this was her second year of doing so. Let me explain: last year was only the first ever run of the Wendover Woods 50 and the first time there had been four races of both distances, and therefore only the first time one could even complete the double grand slam, if one was mad enough to try. Tracey was going for the finish today to become the only person to do this in two consecutive years, or to put it another way, at all. Needless to say, if she finished today her plan was to go for a triple double in 2018. She seemed like a person whose advice was worth listening to.

And her advice was usually “get a wriggle on”. In fact, towards the end of the race I found myself saying that exact phrase, imagining her beside me. I grilled her about the double grand slam and what her training looked like – a pretty consistent habit of 40 mile weeks – and about how to keep eating towards the end of a 100, which is basically to keep forcing food down until you can’t, then carry on anyway. The single most important piece of advice, though, especially from someone on race 16 in the most devilish streak in Britain, was never to take a finish for granted. I was surprised when I first heard her say this, but it really resonated with me when I reflected on our conversation later that night. Me with my relatively feeble experience of ultrarunning had very much been taking the finish for granted. It’s not just in the paltry training, or the lack of practice fuelling mid-run, or the flippancy with which I treat my health. I was running these races like the person who ran her first 50 two and a half years ago – someone in the right state of mind, well trained, healthy and about a stone lighter – not the person I am now. Just like my first two attempts at the NDW100 I hadn’t paid the respect it deserved whatsoever.

The other very key bit of advice she gave me – another bit of advice I didn’t reflect on until it was too late – was this: “This race is more like the first seventy-five miles of the North Downs Way than any other fifty.” How that echoes in my head now.

Lap two was a lot tougher than lap one; proportionally much more tough than it should have been I mean. Perhaps it was the ground underfoot, which was frozen solid when we first passed but already churned up like butter; perhaps it was the fact that halfway through the lap the lead man, a Kenyan runner who had never seen frost before who was running his first ever 50 miler, effortlessly lapped me halfway through his third; perhaps it was the mental effort you find yourself making not to think of the phrase “not even halfway”. Actually none of those are true: certainly the Kenyan runner was one of the most graceful and beautiful sights I’ve ever seen, and it’s hard not to be inspired by someone so skilled at what they do. I quite liked the ground getting softer, even though I managed to turn the same ankle three times on one lap. I suppose the second lap was the first time it felt real.

Lap two took a more reasonable 2:44 including my loo stop at the start. When I passed through base after twenty miles I found that Andy had bagged me a chair – I’m not sure if that’s in the rules – and gratefully took a cup of coffee which I’d texted ahead for, and a couple of cheese sandwiches. For a man not fond of running, discomfort or being away from wifi for more then ten minutes, Andy turned out to be bloody marvellous at crewing. He talked me through the pacing times I needed for the next lap, checked my responses, made sure I’d eaten and drunk and sent me back out without a moment’s faff. It made me up my game. I’m so flippant about these things usually, chatting and having fun and not really paying attention, that being reminded of his own investment in the event embarrassed me a little. Definitely no more messing around after this – if he can hang around for fifteen hours I need to make his time worth it. Off I went again.

When people have asked my why I do ultras, I’ve given a range of answers usually designed to deflect the question because the real answer is none of your business. There is one answer which approaches truth however, and it’s that I believe that to achieve something you don’t just do it once and put it to bed, you normalise it. The Grand Slam this year was to prove to myself (and a little bit, to Andy) that fifty miles was a distance I could break the back of and still have enough to spare – in doing so I’d prove that I can try the hundred mile distance again. If I can make 50 miles normal, 100 doesn’t sound so far fetched, right? What I missed was that, with a challenge of this magnitude, being unfazed by it is different than not taking it seriously. I realised that all this time I’d been scraping through my coursework hoping to get a pass on the exam, instead of getting my head down and studying like my life depended on it. And this race, of all four, was really not the one to busk.

I caught up with Tracey again for a bit on lap three, and noticed that in the previous lap the two ‘halves’ had been pretty much the same time despite the first half being a mile longer, due to the elevation. Good to know – so I could judge my times accordingly. Andy had told me I should be leaving for lap four at around 4pm, so however much earlier than that I got in would go towards getting some food down me. Already food had totally lost its taste for me and I was actively forcing myself to get anything down, but for the first time I wasn’t worried. That morning I’d briefed Andy that a tired and hypoglycaemic Jaz, afraid of the waves of nausea brought on by the thought of food, would trick him and lie about having eaten before and that he would need to force feed me. I know this from past experience, and what’s weirder is that I know I’m doing it but the imperative to avoid throwing up overrules all logic. That said, I wasn’t going to spend another four hours of racing without food or water wondering why I couldn’t move. Andy needed to see me doing OK, but he also needed to make sure I stayed on track.

The first half of lap three passed in an hour and a half, so my times were getting slower but at least it was gradually and consistently. I got a final hug from Ilsuk since he was about to finish his shift, and forced down some Maryland cookies and water as I started the hike up out of the checkpoint. Tracey had pointed out that there were some segments in the second half which had names on Strava, and they were actually signposted on the course – every time I passed them I meant to get photos and every time I forgot. That first climb turned out to be called The Snake, and I’ll let you guess the reason why. Shortly after that we came across Gnarking Around – “It’s a cross between narked and fucking around,” said Tracey – and the final climb with the handrail had a similarly witty name, but I kept forgetting it so simply thought of it as Handrail to Heaven.

Wendy and I passed each other a few times, usually with me catching her on the downhills and her catching me on the ups. I had been prepared for the third lap to be the toughest mentally, but I discovered that the more familiar I became with the course the stronger I felt about it. I looked forward to the known obstacles rather than dreading them – it’s the piddling about on the forgettable flats that make me think I’m going to die in purgatory. Having pushed through the marathon mark my legs found their rhythm and I went into autopilot. I even became (whisper it) quietly optimistic. In fact, on more than one occasion my enthusiastic barrelling down even the more technical and slippery descents earned me a “Well done!” from other runners on my lap who thought I was lapping them; runners who were later confused to find me wombling up the next ascent at slightly less than the pace of an elderly sloth. But I knew my strengths and I knew how to play to them.

The only issue at this point was that my new Altra Timps (bought for their cushioning) weren’t helping. That was weird, especially for Altras; I have little wide-toed narrow-heeled duck feet from a childhood spent barefoot and usually have to go up a size just to fit width-wise, so when I discovered Altra’s toe-shaped toe-boxes and zero-drop I said I’d never look back. The clown shoe Lone Peaks had been doing just fine for me until now, but in my panic I decided I needed something with a chunkier base to help me along on this race. For some reason however Altra decided to shape the Timps like a bloody Jimmy Choo stiletto, all pointy at the front, so they’d started to bash my toes on the downhills. Even wearing them for a few training runs I’d started to notice a pinch, but hoped that was just them wearing in and decided to start with them anyway. Enough of this vanity. I warned Andy I’d be switching to the trusty Lone Peaks for lap four.

The other thing I thought I might need, but really hoped I wouldn’t, was my asthma inhaler. I’d never suffered anything like it until last year when I had to go to A&E with problems breathing during a particularly nasty freelance job and had to be put on Salbutamol to manage it. It was a good few months until my breathing returned to normal, and ever since then the slightest hint of cold has gone straight to my chest and I’ve had to dust the bloody thing off again. I’d managed to avoid the summer cold season, but lo and behold the week before the race I got hit with a respiratory ton of bricks and I’d been relying on the inhaler to the point of almost emptying it. I secretly brought it with me, not telling Andy it was in the bag until I was about to start in case he used it as an excuse to dissuade me from racing. The first couple of laps hadn’t been a problem at all, but as the air got colder and my unfit uphill panting got more pronounced, I knew I’d need to keep it handy.

The pace was, naturally, starting to slow a little by this point, and I got into base when I was supposed to instead of way ahead of the mark. Including the previous pitstop, which again counted in this lap timing, I took 2:53 to complete it – just nine minutes longer than last time. Eating was not exactly easy but I was still managing, and the cup of coffee came up trumps again. Andy bullied me into three cheese and Dorito sandwiches but I had to barter to be allowed to leave with one in my hand, since swallowing all three in one wasn’t happening and I might as well be moving while I eat. Apart from the eating bit, I felt great. I really felt in control. I was almost actively enjoying the race. I got into the checkpoint at five minutes to four, and left it just before ten past – probably too long for a pitstop but I had the time in hand and Andy was wary of my food-avoiding tricks. I got my start-of-lap kiss and my pep talk, switched on the now essential headlamp, and wandered off with a sandwich in my hand like a lost kid on a school trip. And without the inhaler.

As soon as I set off I realised I needed both the inhaler and the loo, but it was just too late for me to turn back to base. Luckily there were public toilets at the cafe about a mile along the course which were still open and I gave myself that mile to hike and eat and catch my breath. The sandwich was going down pretty slowly though; nothing wrong with the food itself, just that my jaw had forgotten how to work. OK, not a tragedy. I took plenty of slugs of water with each mouthful, knowing how easy it is to dehydrate even on a freezing day in late November. As I passed the Gruffalo the second lady passed me; I knew from reports that Cat Simpson was in first place but I had only seen her at the end of my second lap, which coincided with the end of her third, and had somehow missed her lapping me again. It’s just another of the things I like about lap racing, that you see the frontrunners sometimes multiple times and feel the rush of wind as they glide effortlessly past you.

My second loo break (a first for me, I think) seemed to help settle my stomach and reassured me that I wasn’t dehydrating, so I let my legs take over for the downhill first half. By this time we were in the dark, and a pretty profound one at that, since we were often under the cover of trees, so I took extra care with my steps and directions. I was still feeling OK, if a little disappointed that my stomach was already turning, but nowhere near short of calories yet. The first three and a half miles passed without comment and I started trudging up the ascent that would take me up to Go Ape and back down to the checkpoint. It was slow going, but I was still within time.

The eating strategy had become cheese sandwiches at checkpoints and cookies while I walked, keeping a pile stuffed into my pocket. By now I was also sipping at my bottle of Tailwind as the cookies became more and more difficult to chew, and topping up my water bottle at both stops, meaning that I knew I’d have to finish it between stops. It seemed to be working, at least until halfway through that lap. On the climb out of the halfway checkpoint though I started to feel what I can only describe as seasick. Even taking the limited light from my torch into account, the line of the trail in front of me was definitely moving. No time to worry about that though; I’d slowed up quite a lot on this lap already and was slightly over the hour and a half for the first half that I’d hoped to maintain. I pushed on to the Boulevard of Broken Dreams, a long slow descent that leads to the foot of the Snake, trying to keep my balance and not trip over any Gruffalos.

The Snake climb was, surprisingly, a relief from the wobbly horizon – probably because it gave me something to fix on. It was still hard work but a quick systems check told me that my feet were fine – loads better for the change of shoes – my energy levels were fine, even though I was taking a good twenty minutes to chew on a cookie, and my head was still in the game. But my inner ear, that wasn’t at all. The issues with balance were causing motion sickness which meant I had to walk the flats to stop my head spinning, and obviously that meant eating was a struggle. Where had this come from?

When I started to scramble up Gnarking Around for the fourth time, an ascent so steep that if you’re five foot three or less you can be on your hands and knees and still upright, the motion sickness had got much worse. I tried going up backwards which sort of worked for a bit, but in the dark I didn’t trust myself not to stick my ankle in a tree root and go arse backwards straight to the bottom. So, back to the front. The pool of light from my torch had a wobbly halo around it which wasn’t helping, and I even experimented with going without it. Nope. That course in the dark is not a place for experimentation. The end of that lap was a serious struggle. When I reached the gate after the Handrail to Heaven I started lolloping along in what I presumably thought was a sprint, but was must have looked like a drunk donkey missing a leg.

Even so, I was back at base at a quarter past 7, really only three hours and five minutes after leaving. I had a good margin for the final lap – not quite the four hours I was hoping for, but I hadn’t slowed as much as I’d thought. I couldn’t afford to stop for long but I could at least take a few minutes to try to sort my head out. As soon as I passed the timing mat I fell into Andy’s arms, almost knocking over the cup of coffee he held out to me, and told him we had a problem. Straight into business mode he got me into a chair – one he told me I wasn’t allowed to spend long in – and got down to a systems check.

“Andy, I can’t see properly. Everything’s wobbly.”

He did a Knowing face.

“No, it’s not lack of calories. I’m perfectly lucid. I just can’t keep my balance.”

After having to collect me from failed ultra attempts in the middle of nowhere twice before, I was desperate for Andy not to see me in a state. And I wasn’t really in a state, or at least not in the sort of state we’d feared I would be in. This was a totally different situation. He seemed to get it straightaway and to his credit, instead of trying to persuade me to drop out as I thought he would, he ran through the stats and the time I had and started coaxing me back to my feet via a bowl of minestrone soup. The soup was lovely but I could barely focus on getting the spoon to my mouth, and by the time I’d succeeded at that a few times my body temperature dropped dramatically. I needed to get moving.

We walked the few steps out of the tent and towards the stile for lap 5, and immediately I was floored again. I’ve had vertigo before, and this felt like a really monster version of that. Actually, I’ve always had a tough time judging depths and height – it’s why I can afford to be so daredevil on the downhills I think. I can’t work out what’s underneath my feet so I let my feet work it out, and touch wood they’ve never been wrong. This time though they didn’t have a chance. My inner ear wasn’t having any of it. Andy got me back into a chair next to a gorgeous ball of wool which later turned out to be a Labradoodle named Molly and we mooned over her while pretending that I wasn’t about to pull out.

But I knew I couldn’t go on. I wanted that Grand Slam dinnerplate medal so desperately, I’d have walked over hot coals for it; but this wasn’t something I felt I could push through, especially not if I wasn’t going to see anyone for another hour and a half or more. There wasn’t any problem with fatigue or pain or energy or any of those things. I felt awful for Andy who had given up his day to wait in a freezing field for me, who was willing me on, but I couldn’t risk trying to run when every step made me feel like the wrong end of a bottle of Jager. I handed my number in.

The truth was that there are no excuses; I simply wasn’t equal to this race. And I wasn’t angry about it. I hadn’t really trained enough, in hindsight I probably wasn’t fully recovered from the flu, and I wasn’t willing to risk my safety for my pride. It’s a shame that I couldn’t finish it and that I had to forfeit the Grand Slam in the process, but that’s really all it was in the end: a shame. Not a crushing disappointment, not a deep, self-pitying malaise. What I felt, as we drove home that night, was pride. Pride in our little team, which went further towards getting me to the end than I could alone. Pride in Andy for putting aside his misgivings to give me the best possible support, even pushing me to get the finish when I knew he wanted to take me home and be done with it all. Pride in all those who managed to make that final lap, against the odds. Pride in the tireless and incredibly kind Centurion volunteers who make this pro job look like a walk in the park. This little sport of ours is esoteric to say the best, but the people it attracts are all, in a word, superb – something even Andy was able to appreciate. I was proud of the ultrarunning community, even if I couldn’t be part of it this time.

And what’s more, I loved EVERYTHING about this race. I LOVED IT. The format, the people, the hills – yes, the hills – the weather was perfect, the time of year is ideal, the distance is still my favourite and the scenery and terrain was just unspeakably beautiful. I would do this race a hundred times and even if I never finished it I’d still be happy. It’s brutal, but it’s so worth the pain. I’m resisting the temptation to sign up for any more races until I’ve thought long and hard about what I can realistically do next year – but this and Druids (somehow, even though they’re a fortnight apart) are top of the list so far.

My vertigo/disorientation/seasickness/whatever you want to call it didn’t fully lift until Wednesday of that week – the drive home was made that much more exciting by my pointing out hallucinations like bends in the road that didn’t exist, phantom lorries driving towards us and a person walking along the central reservation without hi-viz. I feel like my preparation for these races has been like a game of whack-a-mole: just as I sort one problem another one pops up and I’m back to square one. Another way of looking at that is, I suppose, experience. I might not have made it this time but I feel that much more equipped to work out where I went wrong and do something about it. But most of all I finally feel like I’m moving in the right direction.

I’ve just got a long way to go yet.